what idiot would want to compile c# into mcfunction? (fronttick part 1)

11 Sep 2024I’ve written exactly one post about compilers, so this means I’m allowed to go ham, right? Right?

You have regular programming languages, like c#, java, python, and the like. Then there are the esoteric languages, such as brainfuck, piet, or malbolge.

And then there is mcfunction, Minecraft’s programming language. Somehow, this language isn’t really either of the two. It began as simple commands to modify the in-game world, but it’s grown into an incredibly weird programming language, that you can’t just call a “regular programming language”. On the other hand, the weirdness I’m about to discuss is not intentional, and just grew to be like this, so I’d hardly call it an “esoteric language” either.

Nevertheless, I’m an idiot, and I’m working1 on a compiler “Fronttick” to translate from c# to mcfunction. I have to deal with these idiosyncrasies, and I have no one to blame but myself.

In this series, I’ll discuss some funky things I’ve encountered in this translation process. This time, I’ll discuss the surprisingly annoying issues you’ll encounter when trying to do something as simple as “control flow”.

Gradually increasing weirdness

As noted before, mcfunction did not start out as a fully fledged programming language. You could only put command blocks into the in-game world, and had to use other in-game blocks for program flow. Commands were used more for things like telling the player a story, spawning mobs, etc., than actual programming.

say hi imma scare ya!

spawn creeper 0 60 0

setblock 0 59 0 tnt

Somewhat importantly, there is also a simple scoreboard you could use to store values.

scoreboard players set Atru my_score 3

scoreboard players operation Atru my_score *= Atru another_score

In c# terms, a Dictionary<(string entity, string objective), int> would not be an inaccurate description of this scoreboard. Notably, the entity can be any player or mob in the world, and it does not necessarily need to exist: it can also just be any string, or mobs that have been killed already.

The scoreboard was intended to be used to, well, store scores for simple minigames you would make. Integers are all you get – football scores aren’t in floating point either! Additionally, your only arithmetic options are +=, -=, *=, /=, and %=2. That’s it.

Another interesting feature of mcfunction are selectors. These can be used to select one or multiple entities. If a selector selects multiple entities, the command affects all of them3. The most common selectors are @a (all players), @e (all entities), and @s (yourself).

scoreboard players set @a my_score 3

tp @e Atru

playsound @s block.anvil.fall

So far, so good. We have some non-standard choices, but nothing too out there yet. After all, it’s not yet intended to be a fully fledged programming language, but just to allow people to add some interactivity to their worlds.

In order to not have to spend too much time building physical control flow, an execute command was introduced. Among other things4, you can test for scores, and only do stuff if the test succeeds5.

execute if score Atru my_score matches 10.. say lots of points!

execute unless score Atru my_score matches 10.. say few points...

At some point, the devs realised that it’s a bit (very) inconvenient to have to build all your code in the in-game world. They introduced data packs which have function files.

# File datapack:square

scoreboard players operation @s my_score *= @s my_score

We now have an easy way to square a player’s score, by just making them run function datapack:square.

Naturally, functions can also call other functions. This gets us to one of the most annoying parts of mcfunction. The only control flow is execute if ... and execute unless .... If your conditional code is more than one line, this means that you have to it in a separate function file. This makes it really hard to do simple things, as you’ll have to have a dozen files opened at any time. As a comparison, imagine that every time you create a block { ... } in c#, its contents have to be put in a different file. This is unworkable.

We also run into another problem. There is no concept of a “call stack” in mcfunction, and returning/jumping out of a nested context must be done manually. Consider the following pseudocode.

# File datapack:a

function ...

function ...

execute if ... run function datapack:b

# File datapack:b

function ...

function ...

execute if ... run function datapack:c

# File datapack:c

function ...

function ...

# Suppose we want to "return" here.

function ...

function ...

function ...

function ...

As mentioned, mcfunction files’ branching requires multiple files. To keep things readable, I write the multiple files as nested code blocks instead. However, I also write the multiple files like this for another reason. This code, in a sane language, this would look something like this:

...

...

if (...) {

...

...

if (...) {

...

...

return;

}

...

...

}

...

...

This intuitively tells us something: if we reach the inner statement, and we don’t have a return command handy, all code afterwards gets executed too.

And, unfortunately for us, mcfunction does not have a return command handy6. So unless we do something, the code afterwards does get executed. The way I deal with this is by setting flags whenever we are returning. But doing this becomes really annoying, really quickly.

# File datapack:a

scoreboard players set Ret _ 0

function ...

function ...

execute if ... run function datapack:b

# File datapack:b

function ...

function ...

execute if ... run function datapack:c

# File datapack:c

function ...

function ...

scoreboard players set Ret _ 1

execute if Ret _ matches 0 run datapack:b-cont

# File datapack:b-cont

function ...

function ...

execute if Ret _ matches 0 run datapack:a-cont

# File datapack:a-cont

function ...

function ...

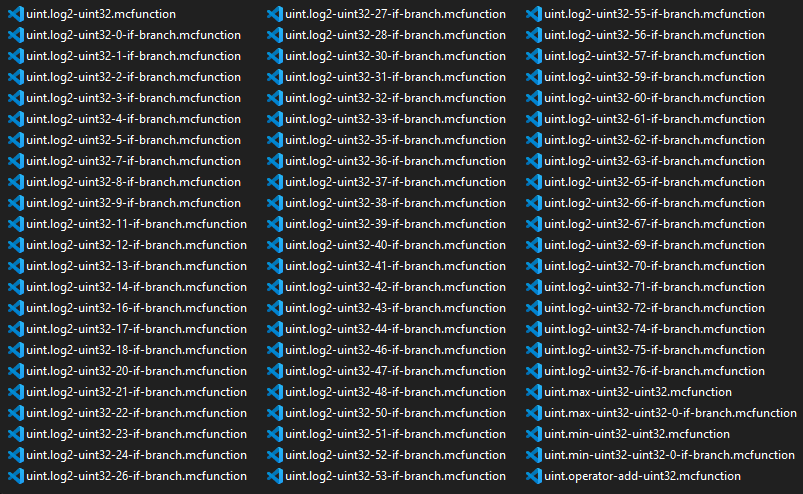

Another consequence of this is that something as basic as a look-up table generates tons of files. Consider for instance the integer log2 function. The “easiest” way to implement this is basically a look-up by if-else-tree, but the amount of files that this requires is insane.

I’m very glad that I did not write this by hand, and that this is instead the output of my compiler. Doing this by hand would be so error-prone it’s not even funny7.

Roslyn

So far, I’ve just been blabbering about mcfunction, but this is a post about a compiler, so I also need to talk about a second language. As I wrote earlier, Fronttick is a compiler from c# to mcfunction, so I ought to spend some time talking about c# as well.

My compiler can be described deceptively simply: take some c# code, and keep rewriting it until it practically looks like mcfunction. Once we’ve done this, we can just linearly go through all code and output all mcfunction files.

A simple example of this process is the following. Suppose we have the following c# code.

static int limit;

[MCFunction]

static void PrintTriangularNumbers() {

int triangle = 0;

for (int i = 1; i < limit; i++) {

triangle += i;

Console.WriteLine(triangle);

}

}

Equivalent (but highly non-idiomatic) c#-code would be the following.

static int limit;

static int i;

static int triangle;

static int cond;

[MCFunction]

static void PrintTriangularNumbers() {

triangle = 0;

i = 1;

For();

}

[MCFunction]

static void For() {

triangle += i;

Console.WriteLine(triangle);

i += 1;

cond = i;

cond -= limit;

if (cond < 0) For();

}

This code can be converted into mcfunction very literally.

# File datapack:print-triangular-numbers

scoreboard players set Var_triangle _ 0

scoreboard players set Var_i _ 1

function datapack:for

# File datapack:for

scoreboard players operation Var_triangle _ += Var_i _

tellraw @a {"score":{"name":"Var_triangle","objective":"_"}}

scoreboard players add Var_triangle 1

scoreboard players set Var_cond _ Var_i _

scoreboard players operation Var_cond _ -= Var_limit _

execute if score Var_cond matches ..-1 run function datapack:for

So how do we rewrite the first c# block that doesn’t look like mcfunction, to the second block that does? Well, we use Roslyn.

Roslyn is an absolutely wonderful piece of open source that gives us access to everything you need to compile c# code. Not too surprising, since it’s the c# compiler. However, unlike everyone else, we don’t target CIL, but mcfunction instead8, so I won’t be using half of its features.

Instead, I’m mostly using Roslyn’s rewriters (and walkers, sometimes) to put the code into the form I want9. These visit every node in your syntax tree, and you can replace nodes with other nodes.

As a simple example of this rewriting, suppose we want to simplify any if (true) and if (false) conditionals.

// Before rewriting

if (false) {

DoStuff();

} else {

DoOtherStuff();

}

// After

DoOtherStuff();

If you visit an if-statement, you check whether the condition is such a literal, and if so, replace the node with its appropriate child block.

public override SyntaxNode VisitIfStatement(IfStatementSyntax node) {

// All VisitX methods work as follows: we walk the syntax tree in

// depth-first order, and whenever the we encounter a node X, the

// method runs. The node will then get replaced by what we return.

if (node.Condition is LiteralExpressionSyntax lit) {

if (lit.Kind() == SyntaxKind.TrueLiteralExpression) {

// When "if (true)", replace the if-statement with just

// its true-block. This is "node.Statement".

// Inside such a block might also be something we need to

// update, so we need to "visit" that too.

return VisitBlock((BlockSyntax) node.Statement);

} else if (lit.Kind() == SyntaxKind.FalseLiteralExpression) {

// When "if (false)", replace the if-statement with just

// its false-block, if it exists.

if (node.Else != null) {

return VisitBlock((BlockSyntax) node.Else.Statement);

} else {

return null;

}

}

}

// There was nothing to update.

// But we might need to update something deeper down the tree. To

// access that, we need this call.

return base.VisitIfStatement(node);

}

This is literally Fronttick code, by the way. My entire compiler codebase is like this: there are a few dozen rewriters and walkers to gradually make very small changes. After enough of those, we reach the format we need to simply “read off” the mcfunction from the c#.

Simplifying control flow

If-statements are pretty easy to translate into mcfunction, as they correspond pretty much directly to execute if and execute unless10. However, loops are much trickier, especially with the break and continue keywords. To simplify matters, let’s first turn all loops into while loops.

As I’ve briefly discussed how rewrites work above, I’ll just specify the rewrites themselves here, without the actual code implementing them. This post would really grow out of proportions otherwise; if you are interested in the code, it can be found in the repo. (Most) of it is commented, even.

The first on the list is the humble for-loop. Turning it into a while loop is pretty easy.

// Before

for (initial; cond; update) {

// Stuff

}

// After

initial;

while (cond) {

// Stuff

update;

}

We can leave break-keywords as is. The continue keyword however needs to be updated, as the while-loop does not automatically run update; any longer on continue. As such, we replace every continue; in the original code with update; continue; in the transformed code.

Do-while loops11 are even easier.

// Before

do {

// Stuff

} while (cond);

// After

while (true) {

// Stuff

if (!cond) break;

}

In this case, we don’t even need to do anything with the break and continue keywords.

Now that the only loop remaining are while-loops, we’re still not done. The break and continue semantics are very non-trivial to implement at this point. For this reason, we go one step further and turn everything into goto.

// Before

while (cond) {

// Stuff

}

// After

WhileStart:

if (condition) {

// Stuff

goto WhileStart;

}

WhileBreak: ;

Now, every break-statement inside the loop can be turned into goto WhileBreak;, while every continue-statement can be turned into goto WhileStart;. After this, the only remaining control flow is if-statements (easy) and goto-statements (“easy”)12.

I’ve already discussed if-statements, but goto-statements are, conceptually, not that bad. We can handle goto by turning each label into a function, and having the goto-statement call said function.

...

label:

...

goto label;

# Function datapack:context

...

function datapack:label

# Function datapack:label

...

function datapack:label

However, it’s unfortunately not that easy.

The goto problem

As I touched upon in the first section, jumping across code in mcfunction gives unexpected behaviour, as there are no stack frames or anything. We need to manually handle “don’t execute this stuff when jumping”. I introduced the basic idea already, but let’s reiterate it here. Suppose we start out with the following code.

// Before

// Label here

{

{

...

{

goto label;

}

...

}

}

// Or label here

We can easily turn this into the following.

// After

// Label here

{

{

...

{

flag = true;

}

if (!flag) {

// Rest of this scope

}

...

}

if (!flag) {

// Rest of this scope

}

}

if (!flag) {

// Rest of this scope

} else {

flag = false;

goto label;

}

// Or label here

If we put the goto and the label in the same scope like this, mcfunction behaviour does not give any problems. The goto label; can be translated to a simple function datapack:code-from-that-label-onwards. In other, more c#-like terms, if we assume the label is at the top, we translate the above in yet another rewrite to the following tail-recursion.

// Afterer

[MCFunction]

static void CodeFromThatLabelOnwards() {

{

{

...

{

flag = true;

}

if (!flag) {

// Rest of this scope

}

...

}

if (!flag) {

// Rest of this scope

}

}

if (!flag) {

// Rest of this scope

} else {

flag = false;

CodeFromThatLabelOnwards();

}

}

We start to run into issues in the more general case, however. First of all, what happens when we have multiple goto’s? A simple boolean flag won’t do the trick any longer. We’ll have to have the flag identify what goto it’s going to. A flag value of 0 represents regular execution. A flag value of 1, 2, etc represents that it’s currently in the midst of a goto to label 1, 2, etc. Let’s sketch out an example to get an idea of what we have to deal with.

// Before

label_1:

{

label_2:

{

{

if (cond1) goto label_1;

else if (cond2) goto label_2;

}

}

}

We only have two simple labels, how bad can it be? Well, it’s not exactly bad, but mostly just annoying.

// After

label_1:

{

label_2:

{

{

if (cond) flag = 1;

else if (cond2) flag = 2;

}

if (flag == 0) {

// Rest of the scope

}

}

if (flag == 2) {

flag = 0;

goto label_2;

} else if (flag == 0) {

// Rest of the scope

}

}

if (flag == 1) {

flag = 0;

goto label_1;

} else {

// Rest of the scope

}

We still have the general idea of “when no goto flag is set, execute the rest of the scope after that check”. However, every scope with a label needs to check for specifically that flag as well. This can add quite a bit of branching. It’s doable, but it’s annoying.

But things are about to get fun. Consider the following code.

{

{

{

label:

}

}

{

{

goto label;

}

}

}

This is illegal in c# as per CS015913. However, there are cases where my compiler generates such code (in a way that’s provably correct)14. So, how to go about this?

{

{

{

label:

}

}

{

{

flag = 1;

}

if (flag == 0) {

// Rest of the scope

}

}

if (flag == 1) {

flag = 0;

goto label;

} else if (flag == 0) {

// Rest of the scope

}

}

Simply put, we repeat the if (flag == 0)-approach up until the finest scope containing both the label, and the goto-statement. This is much simpler said than done, and the method that checks for this,

bool IsFinestScopeContainingGotoAndLabel(BlockSyntax node, SyntaxNode parent, string label)

is code with a complexity of $\mathcal O(\textrm{shit})$ that’s also a 50-line soup of ifs, elses, and foreachs.

This approach is a direct generalisation of what we did before. Indeed, consider legal c# code with a label on the outside and a goto to that label in a nested scope. Now, the finest scope containing both the label and the goto, is simply the label’s scope.

Luckily, like before, this approach can handle multiple possible goto targets just fine, by giving each label its own flag value.

In fact, this flag can be a global variable across the entire codebase. We are either in “regular execution” where the flag is 0, or in “goto mode”, where we just keep skipping code until we find the flag == VALUE check. By the fact that this check is put in the finest scope containing both the label and the goto, we always encounter this check. And once the check succeeds, we reset the flag to “regular execution”, and jump to the target. There is no unexecuted code remaining, as all of that is put away into the else if (flag == 0) part that we didn’t execute.

With this, the bridge between control flow in c# and control flow in mcfunction is crossed15.

Conclusion

When I started with this compiler, there were a bunch of brick walls I saw coming. Custom structs, or non-integer System types for that matter, need to obviously be implemented by hand. Inheritance, generics, those are also always fun when doing ahead-of-time compilation. Selectors? Yeah, those will need some design to be intuitive in c#.

But I was dumb-struck by something as basic as control flow being a pain in the behind. There’s almost no (serious) language on Earth that’s not stack-based. The only thing I can think of that’s actually used in some capacity are Turing machines, but those aren’t exactly the epitome of user-friendliness.

It didn’t help that at the time, I was still kind of getting used to Roslyn, making the process take even longer than it had any right to be. But I did some Very Definitely Proper Testing of this code, and it Works™16.

I don’t think there’s any take-away message here. No-one is going to need to do something like this again, or at least, I hope so. This was honestly just a post for me to rant about my favourite quirk of mcfunction, and the similarly whacky solution.

footnotes and references

-

The present participle is a bit of a bold move, given the last commit was in January… I’m busy, okay! ↩

-

It’ll only be relevant in a future post, but unlike every other programming language, Minecraft’s operators are a bit unique. Division does not round towards zero, but down towards $-\infty$, and the remainder operator does not maintain sign, but always returns the positive modulus. ↩

-

Only if this would make sense, but it’s quite intuitive in which contexts multiple selectors are allowed. You can teleport many mobs to one, but you cannot teleport one mob to many. ↩

-

This command is only rivalled by the assembly

mov-instruction in terms of versatility. ↩ -

I’m using modern syntax, and not the syntax as when

executewas introduced. ↩ -

Okay, as of this year, mcfunction does have a

returncommand, but you can only use it to escape the current file. If you are in a nested context, you still manually need to check whether the context you just leftreturned for you to continue the chain.I’m also disinterested in the

returncommand for another reason: the only types you can return with it arevoidandint. I want to return arbitrary structs, so I need a custom system anyways.(And I just don’t want to rewrite my old code. Precisely this control flow is the most ugly thing in the entire compiler’s codebase.) ↩

-

The c# code is an ugly error-prone mess too, but at least it’s better than mcfunction, because it’s not spread across 64 files. (That, and I just autogenned that code, with some minor tweaks.) ↩

-

You might be wondering, fundamentally, why Fronttick directly compiles into mcfunction, instead of going to some lower-level language for which there already exist compilers into mcfunction, or implementing the CLR in mcfunction myself so that I can just pass the CIL. Certainly, both of these are much easier than what I’m doing! The answer is quite simple; as I mentioned above, regular languages have a call stack. It’s fundamental to nearly every programming language in existence, and just a given on hardware.

But mcfunction doesn’t have a call stack, or scope, or anything of the sort. All variables are global. If you call a function within a function, you just overwrite its own data, which is Very Incorrect. You can implement call stacks by being somewhat clever, but that requires either interfacing with the world, or with nbt, neither of which are ideal: I don’t want the base framework to mess with or assume anything of the world, and nbt is just generally slow.

But when making datapacks, you don’t really need a call stack. If we disallow recursion, we can just make every local variable a unique global variable, and then everything runs correctly. Most people won’t even need recursion when writing code for Minecraft, right? In this case, the trade-off is clear. Disallow recursion, but don’t have the overhead of simulating a call stack.

In the case (non-tail) recursion is actually needed, the solution is simple (but I’ve not gotten around to implementing it yet). Allow for a

[Recursive(64)]attribute on methods that states “this method can be called up to 64 levels of recursion”. The implementation? Just make 63 copies of the method, with each one calling the next, up until the “stack” “overflows”! Yeah, there’s some edge-cases with mutual recursion, but the basic idea just works.Does this generate a ton of files? Yes. Am I beyond the point of where I care about that? Also yes. ↩

-

I did add a small layer of extra abstraction above Roslyn’s walkers and rewriters in the form of

AbstractFullWalkerandAbstractFullRewriterrespectively. The most significant difference is that these can be passed any number of generic walker/rewriter arguments, and the system then guarantees that those arguments have been executed already. This makes the dependencies between the visitors much more explicit. ↩ -

The only thing you need to take into consideration is that you’re checking the same condition in both the

execute ifandexecute unlesschecks if you have both if- and else-blocks. Consider the following code.if (x == 3) { x++; } else { x--; }If you’re not careful, your mcfunction implementation might end up being the following.

execute if score Var_x _ matches 3 run # Add 1 execute unless score Var_x _ matches 3 run # Remove 1In this example, when

x == 3, both commands would end up running! ↩ -

Yes they exist i use them they’re useful they deserve their own syntax. ↩

-

Return-statements can be considered goto-statements to a label at the end of the method, so I won’t mention them separately. ↩

-

Fun fact: in c,

gotoing to wherever is fully legal, but in c++, they realised how terrible of an idea that was. Here I am, going in the opposite direction again. ↩ -

The most prominent example is

return. I have every label increase scope (for reasons I won’t get into), andreturnis put at the end. This gives methods the following shape.label_1: { label_2: { ... label_n { ret: ; } ... } }If any of these outer labels contain something like

if (cond) goto ret;, we get hit with CS0159. Conditional returns are quite common, so I decided it’s the least headache if I just support this. ↩ -

Except for

throw. Orswitch. Orforeach, I skipped over that one because I need so much more for that. Also, uhh, aren’t method calls control flow? Hey, Atru, your post’s unfinished! ↩ -

Slightly more convincing to me is the half-assed mathematical proof in one of the bazillion notebooks on my desk. Can you see it? No. ↩