julia plotter: baby’s third compiler

04 Sep 2024So, the first very iteration of this website had this “Julia plotter” thingamajig. The code’s very old already and pretty darn bad, but if I’m going to write about compilers on this blog, I might as well start with something small and easy. If my memory’s to be trusted, this took but an afternoon, so that certainly seems “small and easy”!

In this post, I’ll discuss this plotter, why you shouldn’t care, the code behind it, and why you should care. I’ll go through everything this compiler needed to work. Now, without further ado, let’s first take a look at the plotter:

- \(z^2 + 0.7i\) is a classic.

- \(z^2 - 0.4 - 0.6i\) reminds me of that brocolli somewhat.

- \(\cos(2z)\) is very spiky.

- \(z^{2\text{acosh}(z)}\) really suffers onder floating point.

- \(z^5 + \text{fract}(|z|)\) gives a cool bubble shape.

- \(|z+1|\cdot z - |z|\) is some weird spear.

- \(z^3 - 0.15z - 0.99i\) gives a bunch of stacked heart-shapes.

- \(z^2 - \text{Im}(z)i\) looks like a bunch of grasping hands.

- \(\sin(z)(z^2 + 1.2 + 0.2i)\) has neat double spirals.

- \(z^2 + 1.1\text{sgn}(\text{Re}(z))iz\) folds into itself nicely at the origin.

In the above visualisation, you can write some math1, and then the plotter plots its Julia set. You can zoom in as you’d expect, and you can focus the image around a different point by clicking there. If your input’s doing something weird, you’ll even get a very vague error message!

Julia sets

Julia sets are a mathematical curiosity part of chaos theory. Consider the sequence $(z, f(z), f(f(z)), f(f(f(z))), \dots)$, where $f$ is a user-specified function. This plotter then simply counts how long it takes each starting point to get “far” from the origin, and colours each pixel based on that.

The motivation for this is that you’ll see only two behaviours for certain functions: your starting point either blasts away to wherever, or it stabilises. Then, once you’re far enough away from the origin, you’re guaranteed to go infinitely far out. I’m completely ignoring this “certain” keyword however, and just letting you use whatever function. As a result, this thing is provably reasonably accurate for all functions $f(z) = z^2 + c$, but all bets are off for anything else. Therefore, the actual mathematical value of this plotter is somewhat limited. Just consider it a “funky picture generator”.

If you want to learn more about Julia sets, the Wikipedia page is pretty understandable, or you could just grab a good ol’ textbook2.

Compilers

With that out of the way, time to get to the point of this post: how I made this. The idea is simple: just write some shader that does the iteration, and depending on how many iterations it takes, give it a different colour.

// For each pixel...

void main() {

// Prep work: handle the viewport to find the what number

// this coordinate represents.

vec2 z = vPosition.xy * exp(zoom) - offset;

z.x *= aspectRatio;

// Actually do the iteration.

// (Stop after some limit, and consider that ∞.)

float iters = 0.;

for (float i = 0.; i < 100.; i++) {

z = /* f(z) — put compiled user code here */;

iters += float(dot(z,z) < 4.);

}

// Colour based on the amount of iterations.

// (This `vSampler` contains a linear Viridis scale.

// I liked a logarithmic scale more.)

float progress = log2(iters + 2.)/log2(102.);

gl_FragColor = texture2D(vSampler, vec2(progress,0.5));

}

What we have to do is “simple”. We have to take some math that the user wrote, and turn it into valid shader code. This is exactly what a compiler/interpreter is for.

Generally, the work of compilers/interpreters can be roughly summarised in a few steps.

First, tokenization: take the user’s text, and turn it into tokens with a lexer3. Instead of working character per character, this allows us to work with significant text blocks instead. For instance a full function may be one token, just like a single mathematical operator -.

This can be done at the same time as the next step if you’re adventurous, but I won’t recommend doing this4.

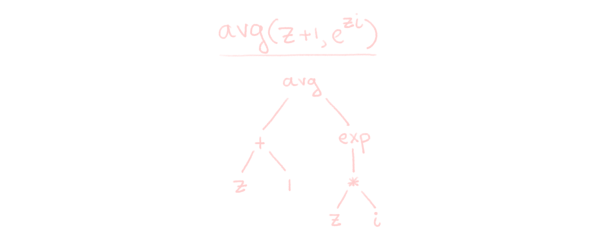

Next, parsing: turn this list of tokens into syntax tree. A syntax tree is the most natural way to analyse a bunch of code; you can ask operators what their operands are, you can ask function calls what their arguments are, etc.

By doing this, you don’t have to care about the textual representation of the code any longer, which is a godsent. Imagine having to account for whitespace every time you wanted to loop over a function’s arguments!

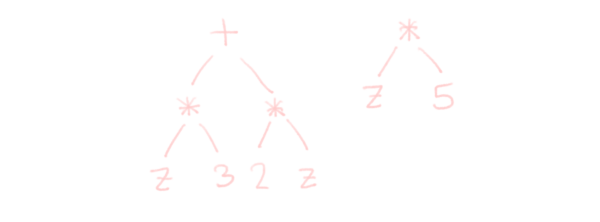

Optionally, you can analyse en optimise the resulting syntax tree. This is usually where the “meat” of a compiler is5. You can do type checking, constant folding, the possibilities are endless.

For example, while the following two syntax trees mean the same, one is clearly more efficient than the other. Naturally, you’d like to always get the more efficient tree:

For this plotter, my optimizations consist of “n/a”, while my analysis consists of determining whether we’re working with real, or with complex numbers, in every node. We do this to catch errors and determine what implementation we need to use for operators. For instance, the “sign” function only makes sense on real numbers, so if the user writes down $\text{sgn}(i)$, we should tell them “no can do”.

The final step depends on whether you’re a compiler or an interpreter. If you’re an interpreter, you walk the syntax tree, executing nodes as you encounter them. If you’re a compiler, you take the syntax tree, and turn it back into text, bytecode, or whatever else is appropriate.

Depending on the complexity of your language(s), this step is either pretty easy or pretty hard. In most cases, it’s the latter. Luckily, in our case, it’s the former.

Let’s go through these steps one by one.

Tokenization

Before we can turn our text into meaningful chunks, we need to decide what those meaningful chunks even are. Of course, we have our variable z, the complex unit i, and numbers 3.14. We also want to allow arithmetic such as + or -. Functions such as sin, re also require us to allow for () parentheses and , comma’s. Whitespace separates tokens. This gives us our full set of allowed tokens.

Now that we have specified what we allow, there is really nothing interesting going on. Consume characters, one at a time, and determine fairly ad-hoc what tokens the recent batch of characters actually are.

In my case, we additionally first do some clean-up before lexing to allow just a slight bit more. Both log and ln are a common way to denote the same function, so replace the one with the other. Similarly, ** and ^ are both common exponentiations, so also unify those. Absolute values |expression| can be turned into abs(expression) with a simple regex, and we also convert pi to its numerical value while we’re at it.

Actually consuming the characters is very simple with our lexer. All of +-*/^(), are always a single token. The only things remaining are numbers and letter sequences. There’s only a few edge cases to consider.

- Mathematicians like not writing the multiplication sign. If we find something like

2i, we will actually output the tokensNumber(2),Op(*),i. Parentheses have a similar problem. - Letter sequences are always function calls, except when they consist only of

iandzcharacters. These also get the implicit multiplication token.

Taking into account these things is arguably not the lexer’s job, but the parser’s, as we’re inserting characters that didn’t exist. However, doing it in the lexing phase is just easier.

In all, in pseudo-pseudocode, tokenization will look something like the following.

Note: The code in this post will significantly differ from what you’ll see when you look at this page’s four-year-old source, for what you’d find to be good reasons.

let tokens = []

while (peek()) {

// Whitespace is insignificant (other than separating tokens).

// Ignore it.

while (peek() === " ")

consume();

let col = get_current_pos();

let c = consume();

// First, single-character tokens.

if (!!ops[c]) { // "ops" contains all op properties by character.

tokens.push(new Token(col, TOKEN.Op, c));

continue;

}

switch(c) {

case ",": tokens.Push(new Token(col, TOKEN.Comma)); continue;

case "(": tokens.Push(new Token(col, TOKEN.Open)); continue;

case ")":

tokens.Push(new Token(col, TOKEN.Close));

// If an implicit multiplication follows, insert it.

// These are )i, )log, )(.

if (peek().match(/[a-z]|\(/g))

tokens.Push(new Token(col, TOKEN.Op, "*"));

continue;

}

// Now, multi-character tokens.

if (is_number(c)) {

let num = consume_number();

tokens.push(new Token(col, TOKEN.Num, num));

// If an implicit multiplication follows, insert it.

// These are 2i, 2log, 2(

if (peek().match(/[a-z]|\(/g))

tokens.push(new Token(col, TOKEN.Op, "*"));

continue;

}

if (is_letter(c)) {

// You can imagine the rest.

}

}

I’ve swept quite some functions under the rug, but they’re mostly self-explanatory. For instance, peek() looks at the next character, while consume() consumes the next character so that we advance further into the code.

After lexing, we end up with a list of tokens. We now need to use these to actually see what our code is doing.

Parsing

The idea behind parsing is simple. Just like how we peeked and consumed character by character when lexing, we will now consume token by token when parsing. We will just keep calling parse_XXX functions depending on what we expect, letting recursion handle the actual tree shape. For instance, a method for parsing a function call might look as follows.

function parse_function() {

let name = consume().value; // The function's identifier name.

let sig = functions[name].sig; // Method signature in `functions`.

let col = get_current_pos();

consume_expected(TOKEN.Open); // The function's opening (.

// Eat the arguments one by one.

let args = [];

for (let i = 0; i < sig.arg_count; i++) {

// We don't care about the specifics!

// Any math is allowed at this point, so just parse that.

args.push(parse_math());

if (i < sig.arg_count - 1)

consume_expected(TOKEN.Comma); // Arg separation.

}

// Final touches.

consume_expected(TOKEN.Close);

return new ASTFunction(col, name, args);

}

// Consumes the next token, and errors when it's not what we expect.

// Allows both a single item, or a list. When it's a list, we need to

// match any token kind in the list.

function consume_expected(tokentypes) {

let token = consume();

if (token === tokentypes || tokentypes.indexOf(token) >= 0)

return token;

error("Something about a wrong token.");

}

Now, if we want to compile some math that looks like max(max(1,2),max(3,4))), our call stack will go parse_math → parse_function → parse_math → parse_function → parse_math before we reach the 1, with each parse_function calling multiple other parse_maths that reach the other three numbers. But by doing the parsing like this, the recursion handles any “jumping around” you’d have to do without, and we can conceptually just walk from left to right. Handling parsing like this is called recursive descent.

These parsing functions return syntax nodes, which all derive from an ASTNode6 base class. Usually, these have children that are also syntax nodes. For instance, the ASTFunction type above is defined as follows.

class ASTFunction extends ASTNode {

/** This node represents a function call `name(arg1,..)`.

* @param {number} col - The call's position in user code.

* @param {string} name - The name of the call.

* @param {ASTNode[]} args - All arguments of the call.

*/

constructor(col, name, args) {

super(col);

this.name = name;

this.args = args;

}

}

This node has a function name, and a list of child nodes that, in order, represent the function arguments.

Continuing on, we implement a bunch of parsing functions, all of which have a similar idea to the above, just with different structures.

// Parse any math — top level, (eventually) calls the methods below.

function parse_math() { .. }

// Parse a single term as part of arithmetic, such as "math+...".

function parse_term() { .. }

// Parse the "+..." as in `parse_term()`'s comment.

// More on this below.

function parse_remaining_expression(precedence, lhs) { .. }

// Parse "+math" or "-math" unary operations.

function parse_unary() { .. }

// Parse a call like for instance "name(math,math)".

function parse_function() { .. }

// Parse a number (including `z` and `i` here.)

function parse_number() { .. }

// Parse a parenthesised expression "( ... )".

function parse_parens() { .. }

Order of operations

Now, the odd duck above is of course the parse_remaining_expression() function. When first writing a parser, you might be tempted to parse arithmetic the same way as you would do function arguments. Just go from left to right, and eat what you get, in order. This would give you the same list of functions, just without parse_term() or parse_remaining_expression(), and the function of interest looks as follows.

// NOTE: This code is fundamentally wrong.

function parse_math() {

// First parse the left-hand side.

// This can only be a unary, function call, number, or ().

let token = consume();

let lhs = undefined;

if (token.kind === TOKEN.Op

&& (token.value === "+" || token.value === "-"))

lhs = parse_unary();

else if (token.kind === TOKEN.Id)

lhs = parse_function();

else if (token.kind === TOKEN.Num)

lhs = parse_number();

else if (token.kind === TOKEN.Open)

lhs = parse_parens();

else

error("Something about malformed arithmetic.");

// We're either part of an arithmetic expression, or done.

if (!peek()) {

return lhs;

}

// We're an arithmetic expression.

// Now we can just consume the operator to know what we're doing.

let op_token = consume_expected(TOKEN.Op);

// The right-hand side may be anything.

let rhs = parse_math();

return new ASTOp(col, lhs, rhs, op_token.value);

}

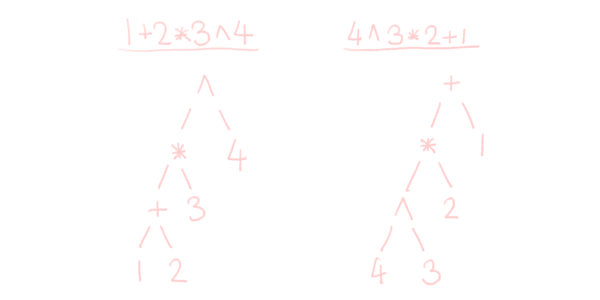

Can you see the problem here? The title of this paragraph may be a hint. The order of operations is off. Consider the two bits of code 1+2*3^4 and 4^3*2+1. The above method generates the following two syntax trees.

In these trees, being deeper down in the tree means that those results are needed (calculated) first. However, exponentiation takes precedence over multiplication, which takes precedence over addition, so the left side does not actually do what you expect; you’re effectively calculating ((1+2)*3)^4 instead. As such, we’ll also need to consider precedence for correctness7.

function get_precedence(token) {

if (token.kind != TOKEN.Op)

return 0;

switch (token.value) {

case "+":

case "-": return 1;

case "*":

case "/": return 2;

case "^": return 3;

}

}

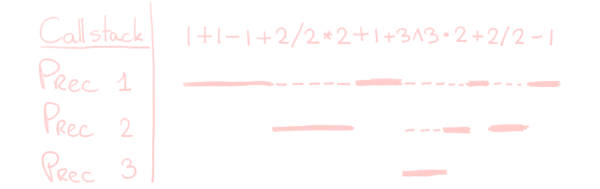

We need a separation in parsing arithmetic that handles a “term” and “the rest”. This allows us to make decisions after every term, to ensure the shape of our tree matches what precedence implies.

Starting at the lowest precedence, we will consider a fixed precedence each time. If we encounter a lower precedence than the current, we stop. If we encounter a higher precedence, we parse that first (which stops when we return to our current precedence, as it’s lower for that higher precedence). Handling higher precedence like this is equivalent to putting the implicit () parentheses around the higher-precedence part.

In code, we get something like the following recursion. It’s a lot of code, but it’s also a lot of comments, so don’t worry. (Or wait, doesn’t that mean you should worry instead?)

function parse_math() {

let lhs = parse_term();

// By default, we start with the lowest precedence (i.e. +-'s).

return parse_remaining_expression(1, lhs);

}

function parse_term() {

// Parse a unary, function, number, or parenthesised expression,

// as in the "wrong" example above, and do nothing else.

}

function parse_remaining_expression(precedence, lhs) {

// The loop is to handle multiple things at the same precedence

// level; cases like "1 + 1 + 1 + ... + 1", and not just "1 + 1".

while (true) {

// We start after a term.

// This may only be an operator, parenthesis (after math in a

// call or parenthesised expression), comma (after math in a

// call), or nothing at all when we're at the end.

if (!peek())

return lhs;

let op_token

= consume_expected([TOKEN.Op, TOKEN.Comma, TOKEN.Close]);

let op_prec = get_precedence(op_token);

// If what comes up next is of lower precedence, it needs to

// be put shallower inside the tree, i.e. parsed later.

// A call where "precedence" is lower will handle this later.

// If the precedence of this operator is 0 (so that it's not

// actually an operator at all), we will always abort here,

// which is what we want.

if (precedence > op_prec)

return lhs;

let rhs = parse_term();

// Again, we're after a term, which may be the end.

if (!peek())

return new ASTOp(lhs.col, lhs, rhs, op_token.value);

// If what comes up next is of higher precedence, it needs to

// be put deeper inside the tree, i.e. parsed first.

let next_prec = get_precedence(peek());

if (precedence < next_prec)

// `precedence + 1` instead of `next_prec`, as otherwise

// "3+3^3*3" doesn't get parsed correctly to "3+((3^3)*3)"

// due to the missing intermediate precedence; you'd see

// the * being treated wrongly as the same precedence as +

rhs = parse_remaining_expression(precedence + 1, rhs);

// `lhs` and `rhs` are now at the same level, so we can safely

// combine the two.

lhs = new ASTOp(lhs.col, lhs, rhs, op_token.value);

}

}

While most of the parsing step consists of fairly easy busywork, accounting for order of operations like this actually requires a fancier algorithm like this. But with this, we’re out of the weeds.

Analysis

For most compilers, analysis is actually pretty difficult. You need to find the answers to questions like “where’s this thing defined?”, “what’s this thing’s type?”, “where’s this read from, written to?”, etc. Luckily for us, we only have one predefined variable, and only predefined functions. We can just build a giant lookup table and read, for instance, that abs is a function from $\mathbb C$ to $\mathbb R$.

The only thing we really need to do, is to know the typing (real or complex) for every node in our tree. This is both to check correctness (as mentioned before, sgn(complex) doesn’t make sense), but also because the implementation of real and complex arithmetic and functions can differ.

This gives the following shape to our lookup table. We need to know the input type(s), which is either "R" real or "C" complex8. Then there is the output type, which is either "R" real, "C" complex, or "M" maintained. This “maintained” type means that complex inputs (generally) give complex outputs, but real inputs give real outputs. For instance, addition works like this. However, sometimes you can get complex outputs with real inputs (sqrt(-1), anyone?), so this distinction is helpful.

Apart from this, we’ll also put the real and complex GLSL implementations into two more columns, in advance. More on this later.

// Okay I actually put these in a custom type with fields "args",

// "output", "glslReal", "glslComplex", instead of arrays, but I don't

// have the space to fit in the constructor calls without an ugly

// scrollbar.

var symbols = {

"+": ["CC", "S", "#+#", "#+#"],

"-": ["CC", "S", "#-#", "#-#"],

"*": ["CC", "S", "#*#", "cMul(#,#)"],

...

"re": ["C", "R", "#", "vec2((#).x,0.)"],

"im": ["C", "R", "0.", "vec2((#).y,0.)"],

"abs": ["C", "R", "vec2(abs((#).x),0.)", "vec2(length(#),0.)"],

"sgn": ["R", "R", "vec2(sign((#).x),0.)", null],

...

}

With this table, every syntax tree node can derive its type from its children’s type, and throw errors when stuff doesn’t match the table.

// The `z` variable.

class ASTVariable extends ASTNode {

...

analyse_type() { return "C"; }

}

// Any function call.

class ASTFunction extends ASTNode {

...

analyse_type() {

let inp = symbols[this.name].args;

let out = symbols[this.name].output;

let has_only_real_inputs = true;

// Check for every argument in the code whether it matches the

// type we expect as described in the symbol table.

for (let i = 0; i < this.args.length; i++) {

let arg = this.args[i];

let type = node.analyse_type();

if (type === "C" && inp[i] === "R")

error(...);

has_only_real_inputs &= type === "R";

}

// Derive the output type from the symbol table and arguments

// we saw in the code.

if (out === "R" || out === "M" && has_only_real_inputs)

return "R";

return "C";

}

}

// You can imagine arithmetic, numbers, etc. being handled similarly.

Output

Finally, we need to create the code that the shader runs. For us, this is simple, and pretty similar to what we did above when analysing our tree. We use the symbol table to recursively insert code snippets to build the full expression. We do this in the same depth-first order as before; a function does not know its code snippet until it knows the snippet of its arguments.

// The `z` variable

class ASTVariable extends ASTNode {

...

get_code() { return "z"; }

}

// Any function call

class ASTFunction extends ASTNode {

...

get_code() {

let code = undefined;

if (this.analyse_type() == "R")

code = symbols[this.name].glslReal;

else

code = symbols[this.name].glslComplex;

// The blueprint has # signs everywhere we need to sub in the

// code of child nodes.

for (let i = 0; i < this.args.length; i++)

// Note that `.replace()` only touches the first # when

// we're working with strings, which is what we want!

code = code.replace("#", this.args[i].get_code());

// All #'s should now be filled in.

// I just assume our table's correct.

return code;

}

}

// You can imagine arithmetic, numbers, etc. being handled similarly.

All that remains is the GLSL code for the real and complex case. There are two reasonable options for representing complex numbers in GLSL as vec2s. In the first case, you encode a complex number $a+bi$ with $a$ in the x-component en $b$ in the y-component. In the second case, you encode a complex number $r e^{i\phi}$ with $r$ in the x-component and $\phi$ in the y-component. I was lazy / flipped a coin / don’t remember, and went for the former without much thought.

In the symbol table, you can see the GLSL code, where we also inserted # signs. These are placeholders where the children’s code snippets get inserted. For instance, function call re(z+z) will first compute its function argument’s implementation as z+z, and then insert that in place of # in re’s complex definition vec2((#).x,0.) so that we obtain vec2((z+z).x,0.) for the final snippet.

Encoding complex numbers as $a+bi$ gives us a lot of operators for free. Of course, you have the arithmetic operators where you only need to implement complex multiplication, division, and exponentiation9, but this decision means that a lot of the real-valued functions func can be implemented as vec2(func((#).x), 0) without second thought. You can see this happening in the symbol table.

Unfortunately, everything else needs to be implemented by hand. This gives us a slew of function definitions in the GLSL code. Worse, none of it is particularly exciting.

vec2 cMul(vec2 a, vec2 b) {

return vec2(a.x * b.x - a.y * b.y, a.x * b.y + a.y * b.x);

}

vec2 cDiv(vec2 a, vec2 b) {

return vec2(a.x * b.x + a.y * b.y, a.y * b.x - a.x*b.y) / (b.x * b.x + b.y * b.y);

}

vec2 cExp(vec2 z) {

float r = exp(z.x);

return vec2(r * cos(z.y), r * sin(z.y));

}

vec2 cLog(vec2 z) {

return vec2(log(length(z)), atan(z.y, z.x));

}

vec2 cSqrt(vec2 z) {

return cExp(cLog(z)/2.);

}

vec2 cPow(vec2 z, vec2 exp) {

return cExp(cMul(cLog(z),exp));

}

...

But once we have these definitions, we can reference them in our symbol table no problem, giving us both the real-valued and complex implementation of each operator and function.

var symbols = {

...

"*": ["CC", "S", "#*#", "cMul(#,#)"],

...

"sqrt":["C", "C", "sqrt(#)", "cSqrt(#)"],

"exp": ["C", "S", "exp(#)", "cExp(#)"],

"ln": ["C", "C", "vec2(log((#).x),0.)", "cLog(#)"],

"cos": ["C", "S", "vec2(cos((#).x),0.)", "cCos(#)"],

"sin": ["C", "S", "vec2(sin((#).x),0.)", "cSin(#)"],

"tan": ["C", "S", "vec2(tan((#).x),0.)", "cTan(#)"]

...

}

Conclusion

With this, we are done. If we go through all four steps above, we turn some math into a GLSL shader of its Julia plot. The plot itself isn’t the most accurate thing, for reasons I’ve touched upon (and for reasons I’ve skipped), but the point was the compilation process anyways.

While I’ve swept some details under the rug, I’ve expanded on most of the things you’d need to write something like this yourself. Something like this really seems like a good compiler project for a beginner to compilers, as the more difficult stuff is simply not applicable here.

The most significant hurdle was the order of operations, which is unfortunately necessary even in the most basic compilers. But once we did that, it was smooth sailing. You don’t need to build a symbol table programmatically to take into account a user’s type definitions, there’s not much reason for code to be invalid, etc.

Of course, this specific project also has a math and shader prerequisite, but there surely you can think of projects with a similar level of complexity that don’t suffer from that. Or projects with a similar level of complexity that are about something you are very familiar with.

Go forth, and write compilers!

footnotes and references

-

I support way too much math. Apart from the standard arithmetic operations, there’s a whole lot more:

re,im,abs,sgn,normalize,ceil,floor,round,fract,clamp,max,min,avg,exp,ln,sqrt,cos,cosh,acos,acosh, and thesinandtanvariants of those. All of these are pretty self-explanatory.Of note is that $\log(z)$ is a multivalued function. Because $e^{w + \alpha\pi} = e^{w + \alpha\pi i + 2k\pi i}$ for any $k \in \mathbb Z$, any complex value has multiple logarithms. I’m using the principal branch: the angle component that’s giving us multivalued problems will be restricted to $(-\pi,\pi]$. This ensures unique output values again.

This multivalued note also holds for the inverse trig functions. These can be defined in terms of the principal logarithm, and that’s exactly what I’m doing, so these pose no problem either. ↩

-

The one I’m familiar with is “An Introduction to Chaotic Dynamical Systems” by Robert L. Devaney. It be good. ↩

-

Least significant footnote on this entire website, but I’ve only just now realised the similarities between “lexer” and the Dutch word “lezer” (“reader”). These words are only 1cm apart on the keyboard. Tsk. ↩

-

You can also automatically generate the tokenization and parsing steps. With these generators, you specify your language’s syntax in EBNF (or similar), and out rolls some code that turns text into a tree. Apparently Wikipedia has a comprehensive comparison between these different parser generators.

However, I like writing my parsers by hand more. I feel like it’s less likely for me to screw up and create ambiguous syntax this way. (I still manage to screw it up sometimes, though.) ↩

-

Just to give you an idea: my very unfinished compiler from c# to mcfunction has around 37 different passes in this step (which excludes everything Roslyn does for me already!). Another compiler for a bullet hell project of mine has around 17 passes. Of course, proper professional compilers blow these numbers out of the water. ↩

-

There’s not really a good place to put it in the main text, but

ASTstands for “abstract syntax tree”. The “syntax tree” part is clear (you have a tree representing your syntax), but the “abstract” part comes from the fact that you’re no longer dealing with literal text. ↩ -

Note that operator precedence isn’t the only thing relevant; operator associativity is too. For instance, is

3^3^3^3interpreted as “((3^3)^3)^3”, or “3^(3^(3^3))”?We humans interpret the exponential operator as right-associative, so we should program the computer to give us the second option. Fortunately, this is the option that the algorithm below will give us, as we’re redefining the

lhsvariable at the end of the loop. Making it left-associative would require you to redefine therhsvariable there instead. ↩ -

I really don’t like doing stringly typed stuff, but in this case it makes this post the most readable. ↩

-

Note that GLSL’s order of operations and mathematics’ order of operations is the same. Yeah, this is a stupid footnote, but this could go wrong if you’re working in a weirder environment, which could force you to write

(#)+(#)instead of#+#. ↩