simd flood-fill goes brrr

21 Aug 2024If I’m talking voxels, I might as well talk about this other fun thing.

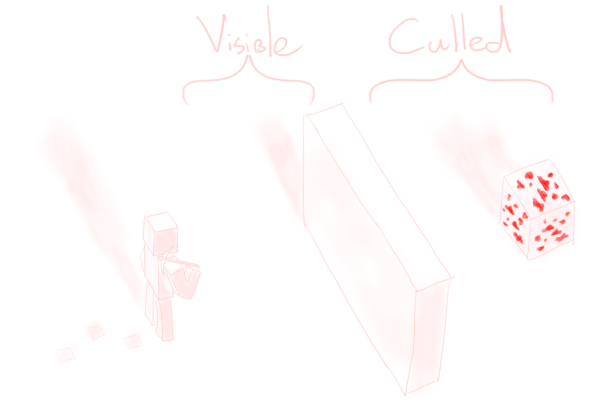

When working with voxels, it is quite important to not render too much. One way of doing this is by culling away subchunks the player cannot see, for instance when something else is in the way.

In this article, quite a funky algorithm is introduced to achieve this culling. One of the steps in this algorithm involves flood-filling through air. Wouldn’t it be nice if this could be done (overly) efficiently?

In this post, I’ll talk about how easy1 it is to use SIMD and bitwise operators, so that you, too, can flood-fill 128 voxels at a time.

SIMD crash-course

Note: Instead of System.Numerics, I will be using Unity’s Burst compiler for the SIMD hardware intrinsics. While the API design is different, it’s pretty self-explanatory, and especially familiar if you’ve written shaders before.

Have you ever thought about the performance implications of byte + byte versus int + int versus long + long? Of course you haven’t, because who would, but it’s a good starting point for this tale nonetheless. If we ignore overflow, doing four byte additions and one int addition is actually pretty similar.

// Four additions, 8 bits each.

byte res1 = (byte)(a1 + b1);

byte res2 = (byte)(a2 + b2);

byte res3 = (byte)(a3 + b3);

byte res4 = (byte)(a4 + b4);

// One addition of 32 bits, with some prep.

int a = a1 + (256 * a2 + (256 * a3 + 256 * a4));

int b = b1 + (256 * b2 + (256 * b3 + 256 * b4));

int res = a + b;

If your arithmetic consists of one operation, this preparatory overhead may not necessarily be worth it… but how often do you do just one operation? Usually, when you’re doing math, you’re doing a bunch of math. And this often involves doing the same stuff, just with different values. If you could speed that up by a factor of four, you would, right?

This is where SIMD (single instruction, multiple data) comes into play. Nowadays, there is quite some hardware support for “doing math on multiple things at the same time”. To mirror the example above, consider the following code.

// Four additions, 32 bits each.

int res1 = a1 + b1;

int res2 = a2 + b2;

int res3 = a3 + b3;

int res4 = a4 + b4;

// One addition of 128 bits, with some prep.

int4 a = new int4(a1, a2, a3, a4);

int4 b = new int4(b1, b2, b3, b4);

int4 res = a + b;

If you look at the corresponding assembly (don’t worry, assembly’s not scary!), you can see the difference between the two clearly.

; Four additions, 32 bits each.

; `Mov`e the ints to where the CPU can `add` them with the other int.

; The four results are found in "eax", "ebx", "ecx", and "edx".

; res1 = a1 + b1;

mov eax, dword ptr [rsp + 8]

add eax, dword ptr [rsp + 16]

; res2 = a2 + b2;

mov ebx, dword ptr [rsp + 24]

add ebx, dword ptr [rsp + 32]

; res3 = a3 + b3;

mov ecx, dword ptr [rsp + 40]

add ecx, dword ptr [rsp + 48]

; res4 = a4 + b4;

mov edx, dword ptr [rsp + 56]

add edx, dword ptr [rsp + 64]

; One addition of 128 bits, with some prep.

; The prep consists of putting the four ints into "xmm0" and "xmm1".

; int4 a = new(a1, a2, a3, a4);

vmovd xmm0, dword ptr [rsp + 8]

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [rsp + 24], 1

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [rsp + 40], 2

vpinsrd xmm0, xmm0, dword ptr [rsp + 56], 3

; int4 b = new(b1, b2, b3, b4);

vmovd xmm1, dword ptr [rsp + 16]

vpinsrd xmm1, xmm1, dword ptr [rsp + 32], 1

vpinsrd xmm1, xmm1, dword ptr [rsp + 48], 2

vpinsrd xmm1, xmm1, dword ptr [rsp + 64], 3

; The actual addition is now just a single instruction.

; The result is found in "xmm2".

; res = a + b;

vpaddd xmm2, xmm1, xmm0

In the top approach, we do four additions add, while the bottom approach only has one SIMD addition vpaddd.

If we now, say, wanted to multiply the four results by the as, the top approach would require four extra instructions. However, the bottom approach would only require one, as there’s a multiplication instruction that handles four ints at a time!

With this, you can see how the latter approach would result in less instructions if your code is doing a lot of math. This is the power of the “single instruction, multiple data” approach.

However, it’s not always immediately clear how you can translate an algorithm from scalar form (working with just ints, floats, etc.) into vectorized form (working with int4s, float4s, etc.). It will turn out that flood-fill, an algorithm where you probably don’t even see the math happening, can be SIMD’d quite well.

2D flood-fill

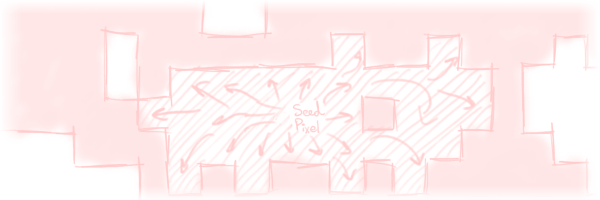

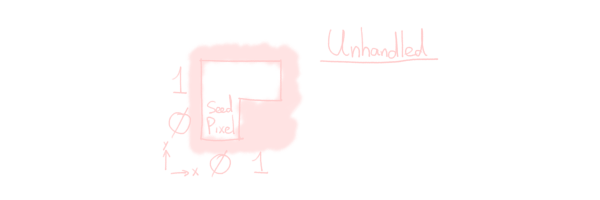

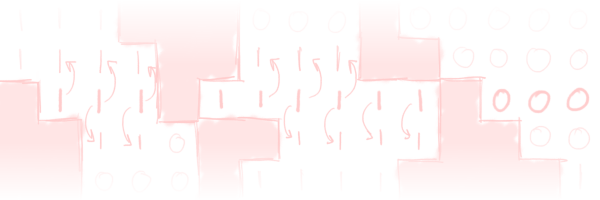

So now let’s start out with the 2D case to introduce this whole “flood-fill” thing. Our task is simple. Our input is a binary image where the pixels are either “empty” (false) or “obstructed” (true). We also have a “seed” pixel from where we start filling. We must then grow this seed pixel to fill as much empty space as we can. Obviously, we cannot move through obstructed pixels.

Note that we are doing a four-connected flood-fill: we only consider the four direct neighbours. The ideas we discuss don’t generalize all that well to the eight-connected case. This case considers all eight surrounding pixels as neighbours, so you can also spread diagonally. More concretely, in the above example, it would mean we fill an extra two pixels.

The standard algorithm for a four-connected flood-fill typically looks something like the following.

(Throughout this entire post, I’ll ignore what happens at the boundaries. This is a fairly obvious implementation detail that would just detract from the rest of the story. If you want to see all the ugly details, they can be found in the repo.)

// Input parameters

// This is a 2D array where `true` pixels are obstructed.

bool[,] image = ...;

int2 seed = ...;

// Output: we set all pixels reached by the flood-fill to `true`.

bool[,] output = new[image.GetLength(0), image.GetLength(1)];

// This contains pixels that may still need to spread to neighbours.

Stack<int2> unhandled = new();

unhandled.Push(seed);

while (unhandled.TryPop(out int2 pixel)) {

// If this pixel is obstructed, we cannot spread to it.

if (image[pixel.x, pixel.y])

continue;

// If we already did this pixel, there is nothing to do.

if (output[pixel.x, pixel.y])

continue;

// Otherwise, mark this pixel and enqueue the four neighbours to

// get handled in the future.

// (This code does not handle the edges of the array well.)

output[pixel.x, pixel.y] = true;

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x + 1, pixel.y));

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x - 1, pixel.y));

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x, pixel.y + 1));

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x, pixel.y - 1));

}

Intuitively, starting with our seed pixel, we grow step by step to surrounding pixels. A full animation of a 2x2 flood-fill is below:

This is not a very efficient implementation. For starters, we’re using a 2D array. Even after being jitted, a 2-dimensional array maintains its 2-dimensional nature, which involves extra bounds checks and all of that fun stuff. Instead of creating a bool[width,height], it would be better to create a bool[width * height], and manually compute all indices x + width * y.

Even if we do this, the order in which we push pixels to the stack is not very cache-friendly either. The last pixel we push to unhandled is (pixel.x, pixel.y-1). So, (assuming everything’s empty), we push, in order, (seed.x, seed.y), (seed.x, seed.y-1), (seed.x, seed.y-2), etc. The corresponding array indices lie width apart. This is not ideal; computers like it much better when you access arrays (at least somewhat) in order. A better access pattern would have the indices lie only 1 apart. We can do this by reordering the pushes:

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x, pixel.y - 1)); // Popped last

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x, pixel.y + 1));

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x - 1, pixel.y));

unhandled.Push(new int2(pixel.x + 1, pixel.y)); // Popped first

Now we push (seed.x, seed.y), (seed.x+1, seed.y), etc., so that the array indices we access lie only 1 apart in the most common case.

Next, this algorithm reads every output pixel once for each empty neighbour, in other words, up to four times. This is fairly suboptimal, and there exist algorithms that do this better. I will not discuss these.2

2D bitwise flood-fill

Finally, there is one more “obvious” optimization we can do to the algorithm in the previous section. The bool type is somewhat inefficient. We use a whole 8 bits to store a single binary value. We can do better than this, and use bit fields.

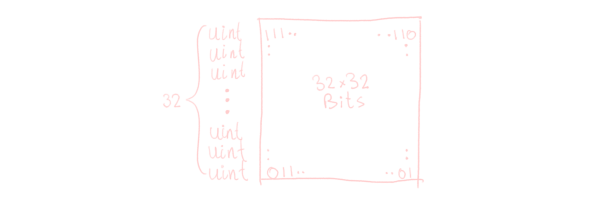

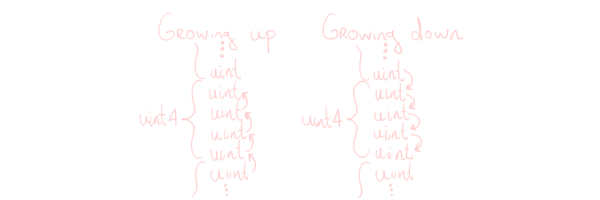

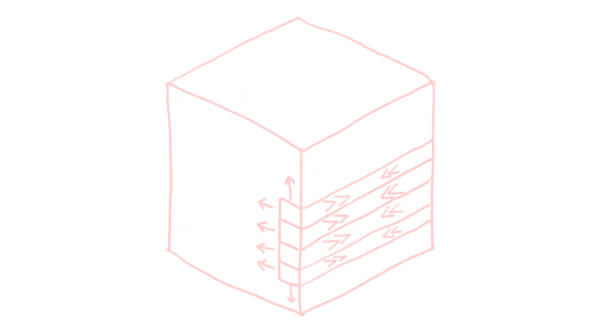

From here on out, we’ll assume that our image is 32×32.3 In this case, we can encode our image as a uint[32]. The array represents the y-axis of the image, while the 32 bits of each uint represent the x-axis of the image.

The unhandled stack only needs to consider the y-axis now. With this, we can grow horizontally very easily: just use some bitwise operators. But while growing the x-axis is easy, the y-axis, less so. Intuitively, to grow vertically, you copy the 1 bits from the current row over to its two neighbours, taking into account their obstructions.

However, this needs the obstruction data from those two neighbouring rows, which requires more array accesses. We can do better by switching our perspective.

To grow vertically, we instead let the current row copy the previous and next rows’ values, and then we take into account the current row’s obstructions. As we also queue those neighbouring rows into unhandled, the effect is the same as the more intuitive approach. But, compared to the more intuitive approach we have fewer array accesses. In code, the full 2D bitwise flood-fill looks like the following.

// Input parameters

// `image` is a 32-length array, where `1` bits are obstructed.

uint[] image = ...;

int2 seed = ...;

// Output: we set all bits reached by the flood-fill to `true`.

uint[] output = new uint[32];

// Initialize the seed in the output directly, otherwise there is

// nothing to copy over.

output[seed.y] = 1 << seed.x;

Stack<int> unhandled = new();

unhandled.push(seed.y);

while (unhandled.TryPop(out int y)) {

// First, grow the x-axis as much as we can.

uint mask = ~image[y];

uint oldRow = output[y];

uint tempRow;

uint newRow = oldRow;

do {

tempRow = newRow;

newRow |= (newRow << 1) | (newRow >> 1);

newRow &= mask;

} while (newRow != tempRow);

// Next, once we can't grow horizontally any more, grow vertically.

// (This code does not handle the edges of the array well.)

newRow |= output[y-1];

newRow |= output[y+1];

newRow &= mask;

// Only propagate updates if we have changed.

if (newRow != oldRow) {

unhandled.Push(y-1);

unhandled.Push(y+1);

}

output[y] = newRow;

}

Now, instead of each horizontal pixel taking an entire loop iteration as in basic algorithm, we simply do some arithmetic. Additionally, our memory usage just became 8× as compact, so this is also much better for the cache.

2D bitwise SIMD flood-fill

The adjectives just keep piling up.

Now that we have a bitwise flood-fill, notice that we are doing math. More importantly, we’re doing the same math for every row. This loops back to what we saw in the SIMD section, and makes vectorization very tempting; why work with uints when you can also work with uint4s?

The code for growing horizontally can stay mostly the same. We only have to update the types, and we only quit growing horizontally once all four uints individually stopped growing. However, the vertical direction is a bit more hairy.

We need to shift the window we’re looking at over by one when we’re copying into the current row. If we simply use either a uint[] or uint4[], this is a bit annoying to do, so we will use aliased pointers.

Additionally, we need to take into account growing vertically within the uint4 as well, and not just to neighbouring uint4s. This comes down to each uint4 rescheduling itself too. At this point, the number of items on the unhandled stack will explode, so you will need a mechanism to prevent duplicates. Vertical growth within a uint4 can also be accelerated by doing three iterations, instead of just one. In all, this results in the following code.

// Input parameters

// `image` points to 32×32 bits of image data in row-major order.

uint* image = ...;

int2 seed = ...;

// Output: we set all bits reached by the flood-fill to `true`.

// Same size as `image`, and should be pre-initialized to 0.

uint* output = ...;

output[seed.y] = 1 << seed.x;

// This time, we will mostly be indexing the SIMD'd values.

// This means that our indices will be divided by 4.

uint4* image4 = (uint4*) image;

uint4* output4 = (uint4*) output;

// "StackSet" is a type with Stack<> semantics, but ignores any

// `Push`es that would add duplicates.

StackSet<int> unhandled = new();

unhandled.push(seed.y / 4);

while (unhandled.TryPop(out int y)) {

// First, grow the x-axis as much as we can.

uint4 masks = ~image4[y];

uint4 oldRows = output4[y];

uint4 tempRows;

uint4 newRows = oldRows;

do {

tempRows = newRows;

newRows |= (newRows << 1) | (newRows >> 1);

newRows &= masks;

} while (any(newRows != tempRows));

// Next, once we can't grow horizontally any more, grow vertically.

// (This code does not handle the edges of the array well.)

uint4* prevRows = (uint4*)(output + 4 * y - 1);

uint4* nextRows = (uint4*)(output + 4 * y + 1);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

newRows |= *prevRows;

newRows |= *nextRows;

newRows &= masks;

}

// Only propagate updates if we have changed.

if (any(newRows != oldRows)) {

unhandled.Push(y-1);

unhandled.Push(y+1);

unhandled.Push(y);

}

output4[y] = newRows;

}

You could further put unhandled on the stack so that we don’t even need to worry about GC. Another optimization would be to use Burst’s Hint.Likely() or Hint.Unlikely() methods to reorder the generated assembly so that you “likely” don’t jump.

If we take a look at the generated assembly that the Burst compiler gives us, we see that indeed, we are now doing SIMD. For instance, the do while loop above compiles to the following assembly:

.LBB4_2:

vmovdqa xmm4, xmm3

vpaddd xmm3, xmm3, xmm3

vpsrld xmm5, xmm4, 1

vpor xmm3, xmm4, xmm3

vpor xmm3, xmm5, xmm3

vpand xmm3, xmm3, xmm1

vpsubd xmm4, xmm3, xmm4

vptest xmm4, xmm4

jne .LBB4_2

The v at the start of each of these opcodes denotes that it’s a vectorized operation, so this loop is full SIMD, just like the c# code. When looking at the full assembly of the algorithm, approximately half of all opcodes are vector opcodes. A majority of the remaining opcodes are control flow, so we have some good SIMD action going on.

Some (bad) numbers

Well, the assembly may look nice, but we’ve still not talked actual numbers yet. So, well, time to do that now. I took the three above algorithms and applied them to the same 10’000 randomly generated 32×32 images. (The full source can be found here.)

- The basic algorithm I described first filled the images in 703ms.

- The bitwise algorithm did the same, taking only 4.56ms.

- And the bitwise SIMD algorithm took… 32.5ms.

Well, this is a bit off. It’s expected that the basic algorithm is much slower than the bitwise algorithm, but the SIMD algorithm ought to be even faster, so what’s going on here?

The problem is the way I did my measurements, which clash a bit with how Unity handles Burst-compiled code. I tested all three algorithms the same way, which comes down to:

for (int i = 0; i < 10_000; i++) {

InitImage();

stopwatch.Start();

RunAlgorithm();

stopwatch.Stop();

}

This seems fair, right? The problem is that in order to run Burst-compiled code, you need to ask the Unity scheduler to run the code. So the actual code that is executed for the third algorithm looks more like:

for (int i = 0; i < 10_000; i++) {

InitImage();

stopwatch.Start();

AskTheUnitySchedulerToRunTheAlgorithm();

stopwatch.Stop();

}

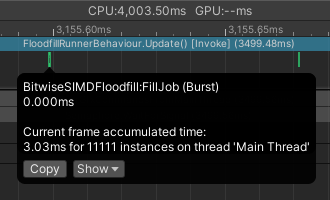

This turns out to have a significant amount of overhead. Unity’s scheduling system is designed to schedule long workloads, few times. It’s absolutely not made for scheduling ridiculously many small workloads, like I’m doing here. Let’s take a look at the Unity profiler.

The actual algorithm is ran during those tiny green specks. In the void in-between, nothing of interest happens. Yet, our stopwatch still counts this time. It would be much more accurate to state that the SIMD algorithm took 3ms, instead of 32ms.

This is still a bit of an apples-and-oranges comparison, however; the first two algorithms have their code jitted by the .NET runtime, while the third algorithm gets its assembly from the Burst compiler. Generally, the former has safety features built in (like array bounds checks) while the latter doesn’t. So our comparison still isn’t completely fair.4

In any case, the speed-up of SIMD is not that significant, giving “only” about a 33% speed-up. The SIMD only really shines during the horizontal growth, but that wasn’t an intensive part of the algorithm to begin with. The vertical growth undoes the effort of SIMD somewhat, as we needed for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) to ensure correctness. That’s a lot of repeated work. The SIMD will become more significant once we introduce a third dimension.

3D bitwise SIMD flood-fill

After spending a significant amount of time blabbering about the 2D case, you’re probably praying that the 3D case is easy.

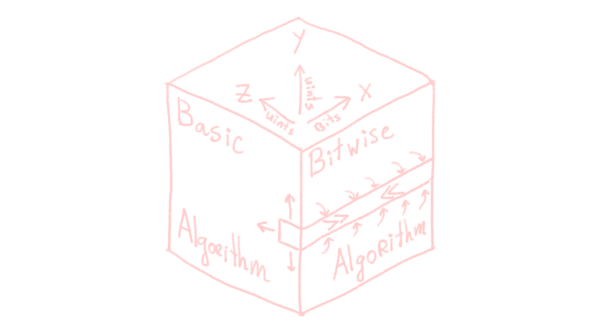

It is. It is just a combination of the above algorithms. Remember how going from the basic flood-fill algorithm to the bitwise flood-fill algorithm reduced our array’s (implicit) dimension by one? Well, adding a dimension increases it again. If we just disregard the SIMD for a moment, we’re actually just applying the ideas of both algorithms at the same time.

Now, add in SIMD into the mix, and you have a party going on.

In 2D, the SIMD did not do that much for us. Within the uints, sure, we grew four at a time horizontally, but vertically, we didn’t really benefit. However, now that we have an extra axis, copying the uints over in the depth-axis fully benefits from SIMD.

The only new ingredient in the 3D case is this depthwise copying of values. This is just like the growth in the vertical direction, but easier, as we don’t need to worry about how we’re shifting within the uint4. This difference is pretty clear in the code:

...

// Vertical growth

uint4* prevRows = (uint4*)(output + 4 * y - 1 + 32 * z);

uint4* nextRows = (uint4*)(output + 4 * y + 1 + 32 * z);

for (int i = 0; i < 3; i++) {

newRows |= *prevRows;

newRows |= *nextRows;

newRows &= masks;

}

// Depthwise growth

uint4* foreRows = (uint4*)(output + 4 * y + 32 * (z - 1));

uint4* backRows = (uint4*)(output + 4 * y + 32 * (z + 1));

newRows |= *foreRows;

newRows |= *backRows;

newRows &= masks;

...

Our indexing has become a bit of a mess though: the horizontal x-axis consists of just one uint with its 32 bits, the vertical y-axis consists of eight uint4s, and finally, the z-axis is divided into 32. Unfortunately, it is what it is. Luckily, if you ever need to do a four- or even five-dimensional flood-fill, the extra axes all behave like this new z-axis, and not either of the two more difficult ones. So at least we’ve got that going for us.5

In pseudocode, the full 3D bitwise SIMD algorithm looks as follows. I’ve highlighted what parts of the algorithm rely on what ingredients to emphasise that there’s really not that much new stuff going on!

// 2D indices as in the basic algorithm.

// No duplicates as in the bitwise SIMD algorithm.

StackSet<int2> unhandled = new();

while (unhandled.TryPop(out var yz)) {

// Growth as in the bitwise SIMD algorithm.

GrowHorizontallyBitwiseSIMD();

GrowVerticallySortOfSIMD();

// Depthwise growth as just discussed above.

GrowDepthwiseSIMD();

if (ThisRowChanged()) {

// Push in two dimensions as in the basic algorithm.

unhandled.Push(DepthwiseNeighbours);

unhandled.Push(VerticalNeighbours);

// Push yourself as in the bitwise SIMD algorithm.

unhandled.Push(yz);

}

WriteUpdatedRow();

}

I’m pretty lazy, so I’m not going to rewrite all of the 2D performance tests into 3D. I’m simply going to grab some performance figures from my voxel project directly:

The Burst-compiled SIMD code takes ~17ms for ten thousand 32×32×32 chunks, while without Burst (so without SIMD), it takes about 250ms.

Again, these figures are not too reliable. This code was explicitly written with Burst in mind, so compiling it without Burst to get a non-SIMD performance figure gets an extra penalty added on top of the lack of SIMD. The note about “this comparison uses two different compilers” from the 2D tests is also valid here again.

This performance is also better than “the 2D-case, times 32”. This is because the 2D tests were made from noise with 80% empty, which is quite complex for flood-fill. However, in my voxel project, I flood-fill large, cave-like tunnels, that are closer to 20% empty, which is much easier. Apart from that, in 3D there are just more ways to go “around” an obstacle, so it’s harder to encounter bad cases.

I’ll just conclude with “would someone (not me) please port BenchmarkDotNet to Unity already” and “the SIMD speed-up is worth the effort here”, and call it a day.

Conclusion

I started writing this post with the idea “let’s just make a quick post on a nice-and-easy SIMD algorithm”, but it ended up quite a bit longer than I expected. I also ended up writing more disclaimers about how the details of performance measurement are significant if you’re not just using some off-the-shelf library.

Nevertheless, SIMD is a really nice way to speed up certain algorithms. In the 3D flood-fill case, one dimension doesn’t benefit all that much with this approach, but the two others do. This allows you to flood-fill 128 voxels at a time, which is quite a bit better than the “one” you start out with, or the “32” you get when you think of the bitwise approach.

footnotes and references

-

Footnote added after writing the full post and looking at the scrollbar: it’s easy, I swear, it just takes some time to get there! ↩

-

See this article for more information. ↩

-

This is not that bad of a restriction. Images smaller than 32×32 can easily be padded with obstructed pixels. Images larger than 32×32 can be handled in a chunked fashion. These chunks then have their own flood-fill-like behaviour: when there are no more updates within a chunk, propagate the changes across the chunk boundaries and flood-fill those neighbouring chunks.

Note that this is also very easy to parallelize! If I were a fan of clickbait, I could even say I’m flood-filling 1500+ voxels at a time on my 12-core machine. Isn’t that just delicious?

The 3D chunks in my voxel project are 32×32×32, so for me, this restriction is not a restriction in the first place. It’s just the natural choice. ↩

-

Ideally, I’d like to use BenchmarkDotNet or similar for this, but that’s not really available for Unity (or Burst). So it’s ad-hoc timing and then reflecting “hey, this timing is whack!”… ↩

-

What do you mean, “no one is ever gonna need 4D or 5D flood-fill”? You gotta dream big! ↩