an intransitive IEquatable<>

14 Aug 2024

// Note!!! This equality is NOT transitive! This breaks a bunch of

// shit you usually wouldn't think about.

A while back (wait, it’s been two years already since I wrote that comment‽), I was tackling the fun challenge of meshing voxels. Today, I decided to write down a hack my brain decided to cook up during that time.

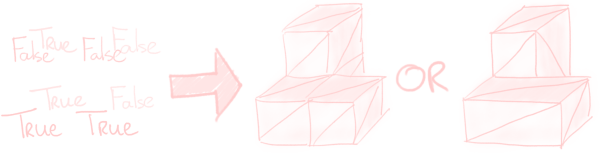

The problem statement is deceptively simple. Given some boolean three-dimensional array of voxels, we must turn it into something the GPU likes: triangles in 3D space that trace out the voxel surface. As an example, consider this tiny 2×2×2 array with some mesh possibilities:

The amount of triangles should not be too large. We don’t want the GPU to choke, do we? In this case, we prefer the right mesh over the left one.

I’ll discuss a more common, and a less common approach for meshing in this post. This second approach is the one for which I used a non-transitive Equals(). Note that this is not a tutorial on how to write a voxel mesher – that is only the context.

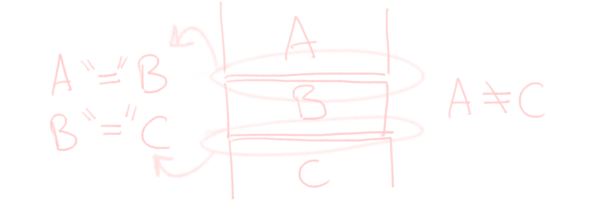

Usually, equality is transitive. This means that if a == b and b == c, you get a == c for free; this matches our intuition. Javascript often gets clowned on because this doesn’t always hold: while "0" == 0 and 0 == [], you have "0" != [], instead of the "0" == [] transitivity would imply.1

This is really just a 2D problem

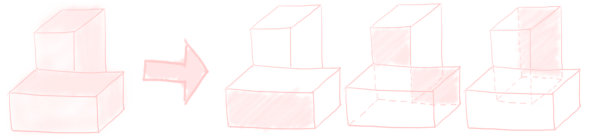

The first step we need to take to tackle voxel meshing, is realizing that this problem is not really 3D. The triangles we create are flat in either the x-, y-, or z-direction. We can just consider a bunch of 2D slices, instead of thinking about a 3D problem.2 For instance, we can divide parallel faces of the previous example into multiple slices.

So, we can reduce the problem of creating a voxel surface, to knowing how to cover some rectilinear polygon with triangles. A rectilinear polygon is a polygon where all angles are 90°, like the highlighted slices above. We also allow holes.

To simplify3 things, instead of working with triangles, we will work with rectangles. This is not optimal, but will end up not being that bad. Our goal is to have “few” rectangles.

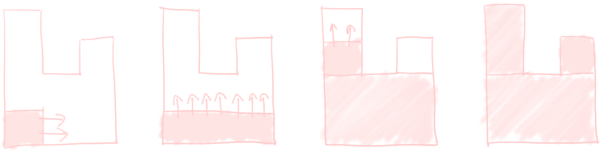

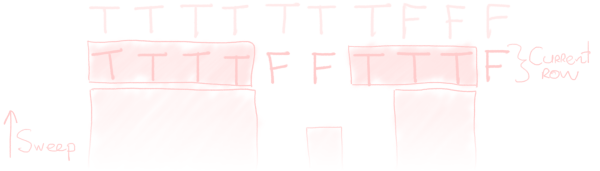

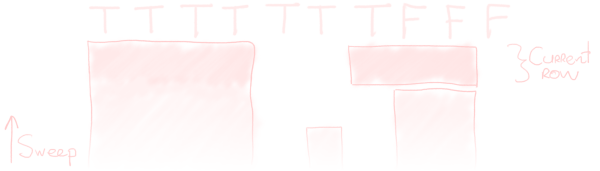

This brings us to greedy meshing. Simply put, greedy meshing starts in some unprocessed 1×1 corner, then tries to grow as much as possible in one axis, and then the other axis. This gives a “large” rectangle, and hopefully there’s now much less to process. As a picture is worth a thousand words, here is an example:

However, as with any algorithm with “greedy” in the name, it’s relatively simple, and likely to be suboptimal.4 While the above example is optimal, there are examples in which this algorithm is bad. An easy example is the following polygon; if you rotate it 90°, the greedy algorithm suddenly lands on a solution that’s worse.

Next, we will make another simplification and allow these rectangles to overlap. This unfortunately results in overdraw5, but we will ignore this. In some situations, this simplification will allow us to reduce the rectangle count even further:

By allowing overlap, we went from three rectangles to only two!

Sweep line algorithms

Now, when allowing for overlap, you may get inspired by the greedy algorithm. You may try to grow rectangles again, this time allowing overlap. Well…

That’s a good idea, actually!6 You do not end up with too many rectangles, and the performance is great. More specifically, if you have $n$ corners, the runtime is $\mathcal O(n \log n)$. Not too shabby.

Well, it’s not too shabby if your implementation is smart. If it isn’t, you end up with a runtime of $\mathcal O(n^2)$ and some tears down your cheek, asking where it all went wrong. Well, probably when you compared each corner with “many” other corners.

The $\mathcal O(n \log n)$ complexity hints at some sorting going on in the efficient algorithm. I certainly don’t know many other problems with that complexity! And indeed, there is some sorting going on. This algorithm is in fact an example of a sweep line algorithm. Honestly, Wikipedia explains it better than I ever could, but let’s give it a shot anyways.

A sweep line algorithm, in general, sorts points along an axis, and then consumes those points in order. Intuitively, you sweep a line from one end to the other, and handle points immediately when you encounter them. Frequently, you will need to use some fancy data structure to not exceed the $\mathcal O(n \log n)$ runtime you encounter when sorting.

The offending Equals()

We will not actually be implementing the $\mathcal O(n \log n)$ algorithm, as its input is different: it assumes that the rectilinear polygon is provided by its $n$ corners, tracing out the polygon. In our case, we have a boolean array representing the polygon instead. In some sense, this means that the “sorting” part has already been done for us.

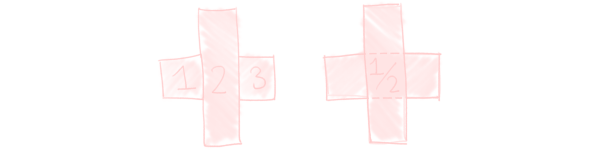

For each plane, we will need to do only one sweep. (If you grow without caring for other rectangles, the sweep direction does not matter.) For exposition, we’ll say the sweep direction starts “down” and moves “up”, increasing in y coordinate.

When sweeping, we first turn the current row into one-high rectangles. The rectangles represent “solid” space, everywhere where the voxel array is true.

Next, whenever we finish a rectangle, we need to check whether this is the extension of a previous rectangle. This can only be the case if an old triangle shares an edge with the finished triangle, exactly. If we find one, we grow it, otherwise we add the new rectangle.

It is this second step in which we will abuse Equals(). In code, this above algorithm looks something like the following.7

// This will contain the rectangles that cover this layer.

// Afterwards, converting these rectangles into triangles is (for the

// most part), easy.

HashSet<RectInt>() rects = new();

// We sweep from "down" to "up"

for (int y = 0; y < CHUNK_SIZE; x++) {

RectInt current = default;

for (int x = 0; x <= CHUNK_SIZE; y++) {

// Step 1: Grow a rect horizontally as far as we can.

// If the previous x-value was "outside", and now we're

// "inside", we have a new rectangle.

if (SteppedInside(...))

current = new() { x: x, y: y, width: 0, height: 1 };

// Otherwise, if the previous x-value was "inside", and now

// we're "outside", we need to finalize `current`.

if (SteppedOutside(...)) {

current = current with { width = x - current.x };

// Step 2: Check whether this rectangle is the extension

// of a previous rectangle. If so, instead of adding it,

// we replace the old one.

if (rects.Contains(current)) {

rects.Remove(current);

current = old with { height = old.height + 1 };

}

rects.Add(current);

}

}

}

We are using Equals() only when we search for an old rectangle to replace in rects.Contains(current). This is where the magic of “find a previous rectangle to grow” happens, and where the specifics of RectInt become relevant.

// An integer rectangle [x, x + width] × [y, y + height].

// These upper bounds are inclusive.

readonly struct RectInt : IEquatable<RectInt> {

public readonly int x, y, width, height;

public int yMax => y + height;

// A comparer that only cares about (x, width), and the two rects

// vertically sharing an edge.

// Note!!! This equality is NOT transitive! This breaks a bunch of

// shit you usually wouldn't think about.

public bool Equals(RectInt other)

=> x == other.x && width == other.width

&& (yMax == other.y || y == other.yMax);

public override bool Equals(object obj)

=> obj is RectInt other && Equals(other);

public override int GetHashCode()

=> (x, width).GetHashCode();

}

This Equals() is non-transitive: if two rectangles vertically share an edge with another rectangle, these rectangles are not necessarily the same.

But this is actually what we want. Because we are using a hash set, nothing “equals” anything else. With our weird definition of equality, this means that no two rectangles in the set perfectly share a vertical border (which would imply we’re not done yet). And because of our check if (rect.Contains(current)), all of our rect.Add(current) actually add something to the set, whether current is updated, or new. This means that we both grow rectangles maximally to the right, and up!

And with this, we are done. Comparing this performance with that of the $\mathcal O(n \log n)$ with $n$ the number of corners is a bit of an apples-and-oranges comparison; that algorithm starts with a list of corners, while we start with binary data. Nevertheless, both algorithms use a sweep, and in both cases, we’re using fancy structures to ensure fast comparison between existing data and new data in the current sweep.

Specifically, this algorithm has a runtime of $\mathcal O(k)$ where $k$ is the number of accesses to the inner loop. With a regular array, this comes down to visiting every voxel, but if you use RLE, you can skip some.

Conclusion

Really, I mainly just wanted to write about me abusing some collections.

This is probably the only time I’ll ever use a weird Equals() and HashSet<>s to achieve something. I genuinely cannot think of another decent approach. The closest would be working with interval trees, but (1) those aren’t in the standard library, and (2) they don’t solve the problem fully. Both come down to “you have to write a lot of error-prone code”.

Sweep line algorithms are a wonderful little corner of computational geometry. These kinds of algorithms really are one of my favorites, because the intuition is just right there. Yet, the problems are often Hard, and the implementation details can be quite tricky. They tickle the brain just right.

Doing something like this in a live codebase requires good documentation. While this kind of algorithm is not likely to change once it’s rooted in your code-base (and properly tested), you never know when someone needs to change something. Encounter this Equals() method with no context, and you’ll likely think it’s just a bug.

In the end, I didn’t even go with this approach. I heavily underestimated overdraw, and the resulting meshes were waaay expensive. Using a greedy partitioning approach with bit fields also had much better cache locality, compared to all the pointer chasing that happens inside a HashSet. So not only did this funny approach generate worse meshes, it also took longer. Ouch.

The code in this post was adapted from my original code, but changed for readability, conciseness, and presentation. I only kept the single funny comment.

footnotes and references

-

Meanwhile, people just don’t care about the much funnier “issue” of irreflexivity that you can find in almost every language. The culprit being floating point:

NaN == NaNis false. In fact, if you try really hard, you can even get0.1f + 0.2f != 0.1f + 0.2fby changing how floats round.(No-one ever does that though, except for the three people that know the words “interval arithmetic”.) ↩

-

Some voxel meshers try to optimize the amount of data sent to the GPU by using triangle strips. Fully making use of these does require some clever 3D thinking. ↩

-

Honestly, this is not much of a simplification. Take a look at the Wikipedia page on triangulation: it is extensive, and you can bet that every algorithm mentioned on that page is implemented in at least a dozen libraries you could use, without having to write a single line of code yourself. In contrast, the rectangular case? Not even close.

The problem with triangles, however, is that they can sometimes become very pointy during triangulation. This may cause issues. ↩

-

Overdraw is when you have a GPU calculate an opaque colour for a single pixel multiple times – you waste all but one computation. Not allowing any rectangles to overlap gives you the problem of partitioning a rectilinear polygon instead of covering one. (Both of these Wikipedia articles are really fun summaries! I appreciate who-ever put so much time into these.) ↩

-

For more information, see “Performance Guarantees on a Sweep-Line Heuristic for Covering Rectilinear Polygons with Rectangles”, D. S. Franzblau, (link).

However, note that I deviate from the algorithm in the paper. This is because of the differences in input: the paper assumes we get a list of corners, ordered by winding around the polygon. We, instead, get a flat boolean grid that describes the polygon. ↩

-

The methods

SteppedInside(...)andSteppedOutside(...)are very dependent on what you structure your data like, how you handle layers, and how you handle access to neighbouring chunks. These details are not really relevant to this post, so I’m sweeping them under the rug here. ↩